On the 25th of May, 2018, the students in the “Archaeology of Cultural Exchanges between China and the West” class started out on their own archaeological adventure to the West; a visit to Dunhuang (敦煌). Dunhuang is a melting pot of cultural exchanges between China and the West, an excellent site for field visit for the class that focusses on the exchanges on the Silk Road. The trip was led by Prof. Giuseppe Vignato, from the School of Archaeology, Peking University.

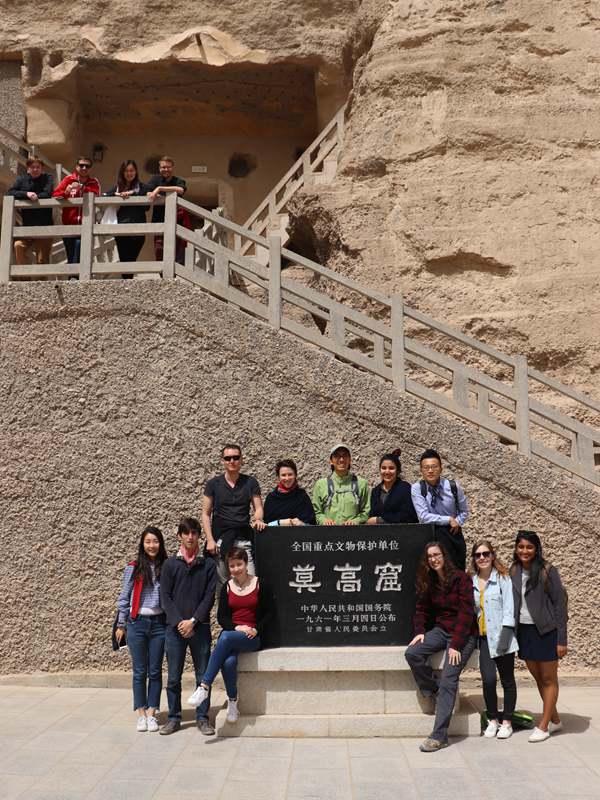

The trip started with scholars visiting the UNESCO world heritage site of Mogao Caves, one of the most important site on the Silk Road and an ancient cave complex for Buddhist activity. The Mogao Caves are a magnificent treasure trove of Buddhist art. They are located in the desert, about 15 miles south-east of the town of Dunhuang in north western China. By the late fourth century, the area had become a busy desert crossroads on the caravan routes of the Silk Road linking China and the West. Traders, pilgrims and other travelers stopped at the oasis town to secure provisions, pray for the journey ahead or give thanks for their survival.

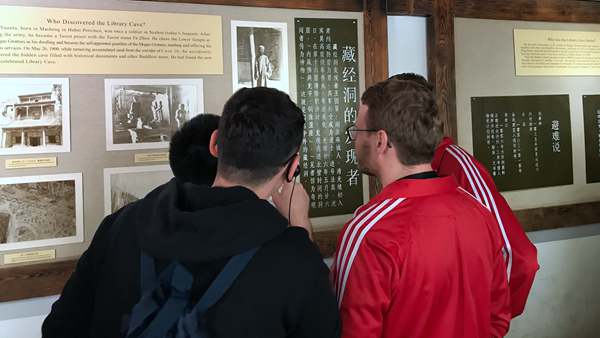

Arranged by the Dunhuang Academy, scholars visited almost 20 caves during their visit; of special interest were the Library Cave (Cave 16-17), and other special caves like Cave No. 45, 220 and 275. Scholars marveled at the beautiful murals and well preserved caves at Mogao. The guide who accompanied was wonderful, and shared numerous details in each of the caves. Erin Dunne (USA) expressed her wonder while experiencing the caves, "Being able to witness 1000+ year old Buddhist art with my own eyes, I have begun to understand both the geography of the Silk Road and the complex idea of how beliefs were exchanged between cultures.”

However, Mogao is not the only Buddhist site in Dunhuang. Scholars also got a chance to visit the Western Thousand Buddha Caves during the trip. The Western Thousand-Buddha Cave, which is situated to the west of Mogao Caves, is set into a cliff on the bank of the Dang River, 35 kilometers (about 22 miles) from Dunhuang City. Because the frescos in this cave are similar in structure and artistic style to those found in Mogao Caves, the Western Thousand-Buddha Cave is considered Dunhuang Buddhist art. Although the exact ages of the caves are not known, there is speculation that this cave may have emerged earlier than the Mogao Caves did.

Along with Buddhsit caves, scholars visited the Han Dynasty Great Wall, Yumenguan Pass (Jade Pass), Yangguan Pass and Cresent Lake; all of which are important sites on the Silk Road. Oriane Gaillard (France) said, "Standing at the Yangguan Pass, with the Gobi desert on one side and the Taklamakan desert on the other, truly made me feel for the courage of ancient silk roads travelers.”

We also had two lectures by distinguished scholars from the Dunhuang Academy, Wang Huimin and Zhang Yuanlin. Prof. Wang’s lecture was focused on the archaeology techniques implemented by Dunhuang Academy to preserve the Mogao Caves, and discussed the improvements in Dunhuang cave methodologies over the past few decades. Prof. Zhang’s lecture was more focused on the iconographical program at Mogao, and discussed the images of Wind-Gods and their origins in Dunhuang murals. Both lectures were extremely informative and helped scholars understand the theoretical aspects of Dunhuang studies. It also enabled them to understand what they saw in the caves, and contextualize it. Many a scholars were seen trying to guess what dynasty the cave was done, based on iconography and style, which showed their learning in the topic.

Catherine Sze (Hong Kong, China) very well summarized her experience, "Looking at mural paintings in the Mogao Caves, I have learned the power of images and iconography to embody narratives and how the religion of Buddhism, as a crucial factor and social glue during the time can inspire art, gather people of different ethnic origins and provide a neutral context for cross-cultural exchange.”

It indeed was an excellent way for scholars to experience what they were learning first hand, and apply their knowledge to understand the Silk Road.

by Vaishnavi Patil