On June 9, Professor Giuseppe Vignato, Professor of Archaeology, Peking University, gave a lecture themed “Buddhist Rock Monasteries of Kucha: A Glass Half Full – What was in the Other Half?” Hosted by Yenching Academy Director of Graduate Studies Prof. Lu Yang and joined by YCA Scholars in the 2021 cohort, this class is part of the Topics in China Studies Lecture Series for the 2022 Spring semester. The lecture explored how Buddhism flourished in the ancient Kingdom of Kucha by investigating the entire rock monasteries and illustrated research on reconstructing the lost parts of the monasteries using archaeometry and scientific analysis.

Prof. Vignato began his lecture with a geographical presentation of Kucha, which preserves the largest concentration of Buddhist remains in Xinjiang, mainly in the form of rock monasteries and more than 800 caves built approximately between the 3rd and 9th centuries. He explained the relevance of the place during the ancient Silk Road, and the movement of people, especially for religious purposes, from surrounding territories, including areas known today as India and Pakistan. Also, he described the role of Kumarajiva, considered one of the most famous persons in Buddhist studies, in the spread of Buddhism in China owing to the monk’s translation of Buddhist texts from Sanskrit and other Central Asian languages into Chinese.

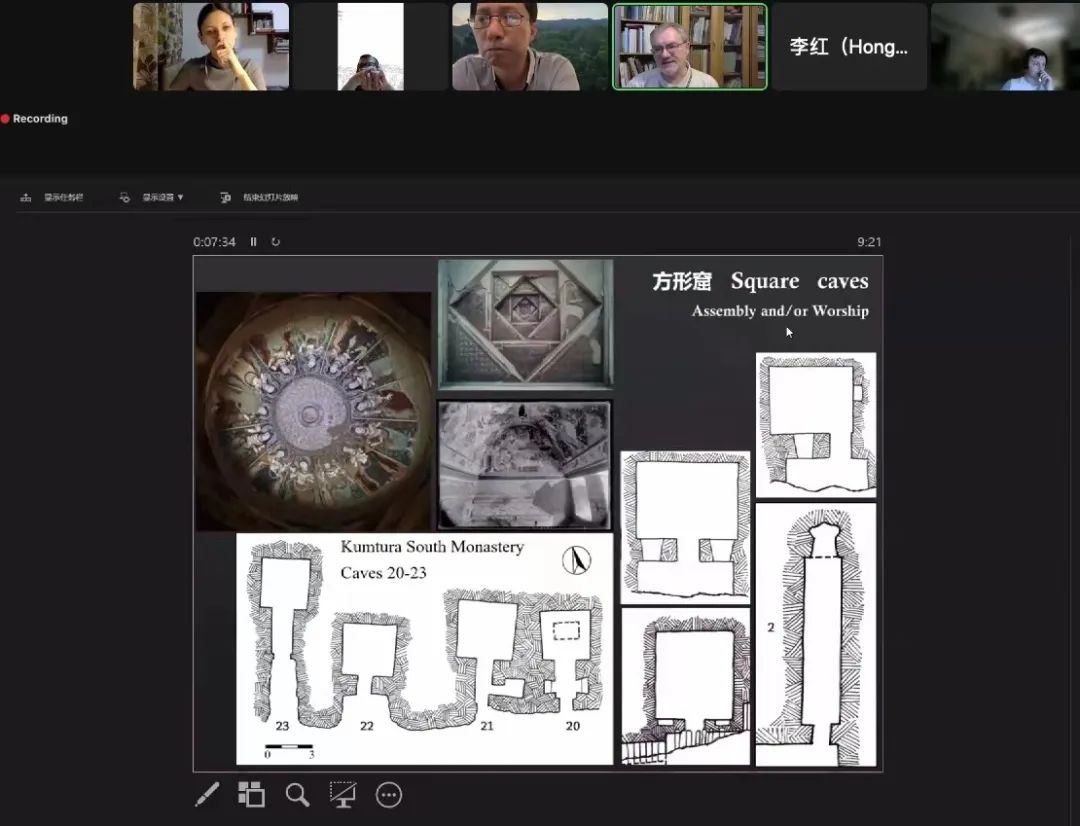

Considering that Kucha was first systematically explored by German scholars of the Silk Road in the early 20th century, Prof. Vignato used many photographs from those expeditions and his fieldwork for visual analysis of the site. He discussed the different types of caves in Kucha, explaining the original principles guiding the constructions of the caves, including their characteristics, dimensions, purposes, and sub-types: central pillar cave, monumental image cave, square cave (with sub-types like niche, assembly and/or worship, meditation cell, lecture hall, and storage cave), and monastic cell.

To understand the interaction between the architectural environment of the caves and how the community of monks and worshippers acted as a devotional to the teachings of Buddhism, the professor analyzed some crucial concepts: boundaries, gates, and ‘empty’ spaces; districts and groups; connective architecture; and space and function.

First, he noted the connection between boundaries, gates, and ‘empty’ spaces, explaining that these elements provided extra information about the likely layout of the monasteries and the way the monks and devotees moved about, especially considering the presence of a stupa as the main object of worship and/or core of the monasteries. Second, Prof. Vignato discussed districts and groups, noting that groups of caves of the same types were often concentrated in a specific area to meet the functional division of the site of providing residences, meditation cells, and ritual spaces to the Buddhist community. Third, he discussed connective architecture, describing the structures (tunnels, stairways, balconies, paths, courtyards, and directions) used to connect the caves. Lastly, he talked about space and functions, detailing how the caves were used for religious functions like circumambulation, the procession of images using palanquins, worship of relics, railing and ritual table, sounds and chanting, and incense or oil which created soot found on the caves’ paintings and ceilings.

Yenching Scholars raised several questions during the question-and-answer session. One question concerned the nature of the workforce assembled to make and install the massive statues. Prof. Vignato responded that carpenters were mostly needed at Kucha since the enormous statues and caves in Kucha were made out of mud with wooden structures to hold them – quite distinct from other sites across Central Asia where the core of the statue was made from rock. He also referred to new research findings that a famous Uyghur statue and one found in Kizil, Kucha, were created from the same mold after a three-dimensional scanning was conducted; hence, providing valuable information on techniques and the possibility of a mold being used for centuries and hundreds of kilometers far away.

Another inquiry was whether the soots on the cave ceilings and paintings resulted from religious practices in the ancient times or the activities of people who found and lived on the site in the last century. Prof. Vignato explained that a thorough scientific study like carbon-14 dating is needed to determine the composition of the soot, which can also provide insights into how long the caves had been used. Nonetheless, he added that he identified three types of soots from his fieldwork analyzing the caves: greasy and wet (as a result of oil burning from a lamp), dry (from burning materials that do not emit much smoke, e.g., dry animal dung), and protein soot (perhaps, as a result of the cooking activities by shepherd and farmers who stayed in the caves when the Germans began their exploration over a century ago).