On June 10, Yenching Academy held a lecture, Films Today: A way to Imagine China and Ourselves, as part of its Topics in China Studies Lecture Series for the 2022 Spring semester, taught by Professor Dai Jinhua, Department of Chinese Language and Literature at Peking University. This class was hosted by Yenching Academy Associate Dean Fan Shiming, and Yenching Scholars joined the online session. While reminiscing on the technological revolution, digital transformation, the “death of film,” and cinematic art, Prof. Dai explored the history of Chinese cinema and the culture-bound syndrome stemming from the cultural construction process of Chinese movies.

Prof. Dai began by reviewing the contributions of André Bazin, French film critic, author of What is Cinema? and co-founder of the film magazine Cahiers du cinema, to the development of cinematic art and aesthetics. She explained that examining the topic of motion pictures is crucial because it is not only concerned with aesthetics but has been one of the most extensive mass communication and cultural tools shaping reality and collective memory. Nonetheless, the global movies industry has experienced some challenges over the years, resulting in talks about the “death of film culture.” Prof. Dai noted that this idea had been increasingly debated, especially in the last two decades, with the rise of digital alternatives and technology platforms promoting short videos made with hardware like smartphones and the fall of Kodak.

The speaker noted that the emergence of Chinese movies on the global stage is closely linked to China’s growth over the years, with the nation providing a massive consumer market base and overwhelming capacity in manufacturing and demand for 3D filming technology. Considering this transformation in a short time, Prof. Dai challenged the students to ponder the prospects and pathways the Chinese film industry can offer for further development of digital films and the global film industry.

By reviewing several writings and movies, including Diary of a Madman by Lu Xun and One Second, and Hero by Zhang Yimou, Prof. Dai discussed the history of Chinese films. She noted that the significant difference between the Chinese and the Western movie industries is the absence of the logic of the continuance of history constructed on capitalism and modernization as an effective way of expression. The guest lecturer stressed the efforts of Chinese movies and writings in reflecting on China’s pre-modern history and the denial of the culture and history after the new cultural movement in 1919. “This idea of self-denial entailed giving up on the pre-modern history to create the modern history of China … through movies, literally works, … and modern Chinese language,” she added.

Prof. Dai explained that this reflection of history extended into the 1950s, 60s, and through the 80s, as witnessed in many movies and writings, including Jin Guantao’s Super-stable Structure and Evolution of Chinese Political Culture and Xu Bing’s Book of Heaven. She mentioned that this duplication of the ideas prevalent in the May 4th movement in different movies and literary works represented the lack of a linear concept of history in China. Nonetheless, the rise of modern China evoked a psychological fact for the Chinese people. Prof. Dai mentioned that Chinese history entered a contemporary era of active cultural undertakings, resulting in the recycling and re-narration of ancient Chinese history that focuses on truth-seeking, dynastic shifts, and weird worship of power comprehensively portrayed through movies.

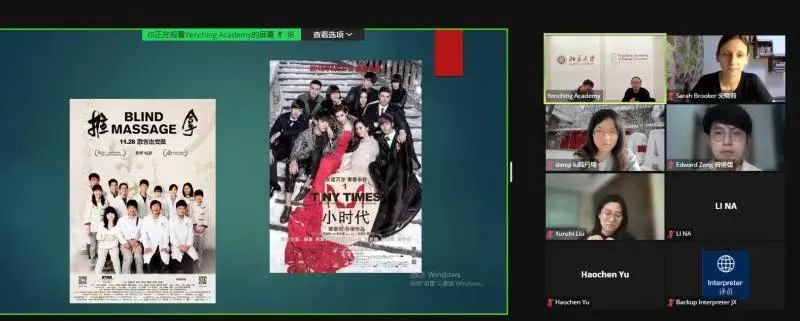

The speaker analyzed the movies Blind Massage and Tiny Times to describe the nature of current 21st-century films considering the historical changes and focus of Chinese cinematic art over the years. Prof. Dai explained that the two movies tell a single story about visuality for marginalized people, about making the unseen seen. In this vein, the movie industry – the combination of lens, sound, and pictures – has become a powerful tool for sharing the experiences and imaginations of all peoples. She reviewed other Chinese films, including The Piano in a Factory and Ip Man, noting that the actors and their expression of Chinese culture via language and body movements have created different editorial possibilities and cinematic aesthetics that differentiate the Chinese film industry from the West.

Prof. Dai’s lecture peered into Chinese movies as an art and a window into historical changes and social structure. She noted that there is the need to think about how we review and reshape Chinese history and place ourselves (or the concept of people) within that history, especially when we consider the nature of the globalized world where China has emerged and the disruptions imposed by the pandemic. Awareness of the changes and voids will shape our perception and understanding of the meaning and future of Chinese cinema.

Several scholars raised questions following Prof. Dai’s lecture. One question was about the changing relationship between language, power, and bodily expression. The lecturer responded that the relationship between power and body has become more direct, but it could become obscure in the era of surveillance. Also, the professor clarified that the concept “body” discussed in the class drew on the Western meaning of the concept, which China loaned. Body, as used in the Chinese context, relates more to pleasure; it is a mental image rather than an object image. Hence, the transition towards the surveillance age enables those with power to bother less about changing how people think; instead, they achieve their purposes by changing the “body” through rewards and restrictions.

Another question centered on the possibility of cinemas changing widespread social biases and promoting political correctness. Prof. Dai discussed that the motion industry had prompted the reflection on existing social prejudices and the need to end discrimination and marginalization. Yet, such changes have mainly been rhetorical rather than fundamental. She explained that the Chinese film industry has been evaluating its process of internalizing and criticizing the logic of political correctness while avoiding the blind replication of the process in the West. She also discussed that the issue of political correctness in Hollywood could be observed in changes in the Academy Awards and its response to requests to be more inclusive and cover different vulnerable groups. She added that the crisis and decline of American cultural hegemony had made the idea of political correctness more apparent, and helped Hollywood continue having a strong voice in the global film market.